<< Back to Tomas Hirschfeld details Recent Remembrances of Tomas B. Hirschfeld |

Bruce ChaseDuPont Fellow, E.I. DuPont de Nemours (retired) and Research Professor, University of DelawareI first met Tomas Hirschfeld in 1977 at the International Conference on Fourier Transform Spectroscopy, held in Columbia, South Carolina. I was two years out of graduate school and overwhelmed by the leaders in the rapidly growing field of FTS. I quickly saw that whenever there was a group of people talking animatedly, Tomas was always in the center (though you could not see him from the outside!). Tomas seemed to know almost everything about almost everything. I was fortunate to get to talk with him, and we served on the organizing committee for the next FTS meeting to be held in 1981. My position at DuPont allowed me to attend multiple scientific meetings each year, and whether it was FACSS, Pittcon or international spectroscopy meetings, I always found a way to sit down with Tomas and just talk. The FTS meetings in 1983 in Durham and 1985 in Ottawa were especially exciting. Since both of us had access to interferometers for infrared work and lasers for Raman, many of our conversations were focused on the possibilities for exploring coupling of interferometers and lasers to find out whether FT Raman spectroscopy was feasible and useful. These discussions led us both to try and put together an FT-Raman instrument; Tomas at Livermore, and Bruce at DuPont. There were more than a few phone calls and faxes going back and forth. It was a wonderful friendly competition resulting in success on both the west and east coasts. Sadly, Tomas had very little time to enjoy our joint success. I will always treasure the chance I had to work with and publish with Tomas. While his scientific understanding and knowledge base was boundless, what I really grew to appreciate was his curiosity. Tomas wondered about everything. Life with Tomas was never dull. In fact, I ended up in an uncomfortable conversation with management after the "IR-100" Award for FT-Raman. You see, the first I knew that we had even submitted the idea to Industrial Research was the notification that we had won. Since all external publications were supposed to go through a clearance process, this caused some feathers to be ruffled. However, they could not very well decline the award, so all ended well. Looking back, I feel certain that my scientific career would have been significantly different without the influence of Tomas Hirschfeld. |

Peter GriffithsEmeritus Professor of Chemistry, University of IdahoI worked for Block Engineering from 1969-1970, both before and after they split off Digilab as a separate division. The two divisions didn't interact very much; I worked for Digilab and Tomas worked for Block. Nevertheless, I tried to at least keep up to date on Tomas's projects that weren't classified. One of them was the development of a mobile remote Raman spectrometer, mounted in a large truck. As usual, he was ahead of everyone else. Remember this was 50 years ago! A truck-mounted remote Raman system tested at LLNL. It is monitoring the plume being released from the smokestack in the background of the right hand photo. Courtesy of M. Angel. I first encountered him when I was a post-doc in Ellis Lippincott's lab at the University of Maryland and Tomas was visiting. He met with Ellis's research group for a couple of hours and, as I found to be his SOP, he discussed every topic that people raised. One of the grad students, John Lephardt, wanted an internal reflection element with an (at that time) unusual refractive index. I can't remember what Tomas came up with but for the sake of argument I'll say it was barium titanate. Tomas immediately gave the refractive index to four decimal places and the reference of the paper in JOSA where it was given. The only problem was that after giving the authors' names and the year of publication, he paused and admitted that he couldn't remember the page number "but it was a third of the way through the journal and started on the left-hand side"! As a final note, when I worked for Block/Digilab, I had occasion to see Tomas's filing system in action. It was the same as his system at LLNL! An amazing man! |

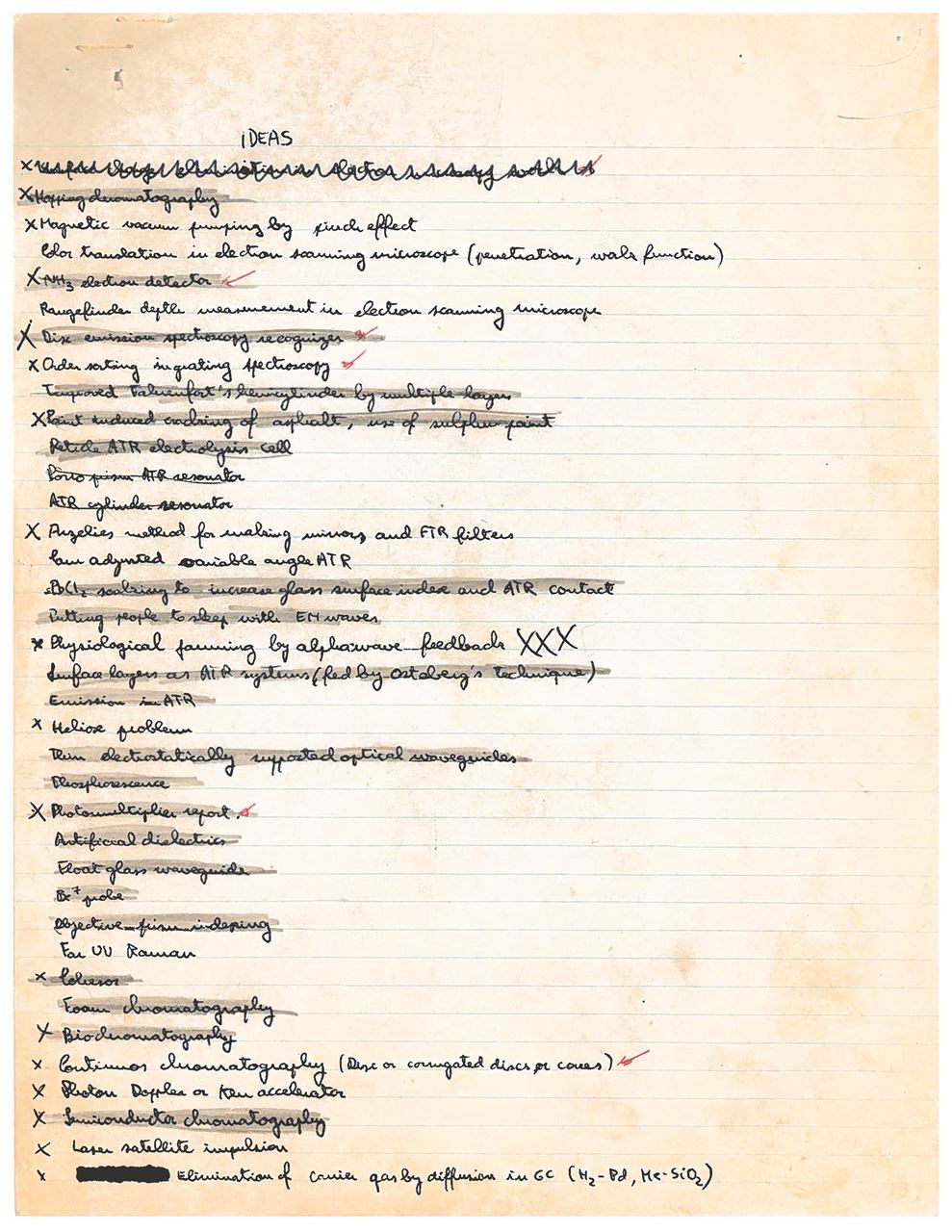

Gary M. HieftjeDistinguished Professor and Robert & Marjorie Mann Chair, Dept. of Chemistry, Indiana UniversityTomas Hirschfeld: Analytical Chemist Extraordinaire My first acquaintance with Tomas Hirschfeld was through Gary Horlick, when Gary and I were still in graduate school at the University of Illinois. Gary had spent the summer at Block Engineering, near Boston. Gary’s interest had turned to Fourier Transform infrared spectrometry, and Block was in the process of introducing the first commercial instrument in that field. At Block, Gary met and worked with Tomas Hirschfeld and later introduced me to Tomas at a conference, as I recall the 1969 Pittsburgh conference, held that year in Cleveland, Ohio. I was struck immediately with Tomas’s energy, range of knowledge, and inventiveness. My acquaintance with Tomas grew steadily, mainly through encounters at other conferences, so when I accepted a faculty position at Indiana University, I suggested Tomas as a speaker in our analytical chemistry seminar series. In short, Tomas’s lecture was unique and a tremendous hit with both students and faculty. Unlike almost all other speakers, Tomas arrived without projection slides (PowerPoint was not even a dream at the time) and provided a title that permitted almost unlimited flexibility. After I introduced him, he walked to the blackboard in front of the room and wrote down a list of six topics. He then asked the audience to suggest which topic or topics he should cover. Without notes or visual aids, he then went through three of those topics before the seminar period expired. Not surprisingly, Tomas’s visit to Indiana was a resounding success. At that time, our chemistry department had a program to invite scientists in industry to accept a limited-term adjunct professorship. Each “Industrial Professor” was then invited to visit our department whenever and as often as his/her schedule permitted. Local expenses were covered by the University. My nomination of Tomas for such a position was unanimously endorsed by our faculty, which resulted in an appointment and Tomas visiting 2-3 times each year, typically for a period of 3-5 days. During each visit, Tomas presented at least one lecture, always in the same style described above, and always with a new list of topics (ones listed in earlier lectures but not used were deemed by Tomas to be “old news”). He also met with many of our faculty and students, which resulted in a number of collaborations and joint research projects. Our earliest joint research with Tomas was in the area of Near-Infrared Reflectance Analysis (NIRA) and involved one of my graduate students, David Honigs. Tomas was at that time consulting with Technicon Corp., of “AutoAnalyzer” fame, but which was embarking on a product line in the NIRA area. Tomas arranged for a couple of the Technicon NIRA instruments to be “loaned” to our lab (they were never returned) for use in David Honigs’s research. David and Tomas remained in close contact between Tomas’s visits to Indiana, so David really became more Tomas’s student than mine. That collaboration led to a total of 8 publications and spawned additional projects that were carried on by three later students, yielding a total of 18 published papers in NIRA. Those studies would never have been initiated had it not been for Tomas’s influence. In other narratives in this series of anecdotes about Tomas Hirschfeld will be found references to the tremendous file of research ideas he generated. Yet, he confided in me once that he possessed a terrible auditory memory but an excellent memory of written material. How, then, was he able to accumulate such an enormous written file, when many of his ideas, of his own admission, came while listening to lectures by others? The secret could be gleaned from a glance at Tomas’s shirt pocket. In that pocket, he always carried a note pad of miniscule dimensions (I would estimate 2” X 4”) and also a cluster of several #3 lead pencils. On the pad, he would routinely record his thoughts and ideas. But how could he provide the needed detail in such a tiny space? The answer: “differential writing” (his own term) and extremely sharp pencil leads. He had mastered a method of moving the elbow of his writing hand forward while simultaneously moving the fingers of that hand backward, to provide very minute movements of the pencil tip, somewhat akin to the mode in which a differential screw operates. The several pencils were needed to make sure that at least one retained the requisite sharpness to generate microscopic letters. Several examples of TBH’s tiny notes. These particular pages are approx. 3” x 6”. Courtesy of M. Angel. We at Indiana University had dreams of attracting Tomas full time to Bloomington and made several attempts to have it happen. However, when he elected to leave Block Engineering he decided to relocate to Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Although I was disappointed that Tomas would not be my colleague at IU, I was happy with his Livermore decision since I had for some time been a consultant there. During those days, Tomas and I, along with a number of highly talented scientists at LLNL, pursued additional projects, some of which generated spinoff efforts that were taken on by my students. A number of them involved the use of fiber optics for chemical sensing, a field that I credit Tomas as starting. One of his pronouncements involving remote analysis has always stayed with me. Tomas said “There is always a need for doing analysis at a place where you are not. For example, when your sample is a chemical warfare agent, local analysis methods would tell you ‘you are dead’.” Other pithy sayings of Tomas can be found in the compilation published by David Honigs in the August, 1986 issue of Applied Spectroscopy (see Honigs, D., Appl. Spectrosc. 40(6), page A11 (1986). [Note: These sayings are collected on the “Tomasisms” page.] Others in this series of comments have commented on the fact that Tomas Hirschfeld died very early, I believe at the age of 46. Tomas himself recognized that his weight might lead to a shortened lifespan. However, he was very philosophical about it; he stated that he was merely living in the wrong period of history. A few hundred years before, those who enjoyed Tomas’s girth were among the longest living; most others died of malnutrition or maladies derived from it. Tomas Hirschfeld was perhaps the most talented individual I have ever met; I benefitted tremendously from interacting with him, as did many of my students and colleagues. We in the analytical chemistry community are extremely fortunate to have been able to count him among us. It is a pity that later generations cannot experience firsthand his intelligence, drive, insight, and range of knowledge. Hopefully, the testimonies in this group of essays will encourage newer generations to obtain at least a glimpse of this remarkable person and the many contributions he made. |

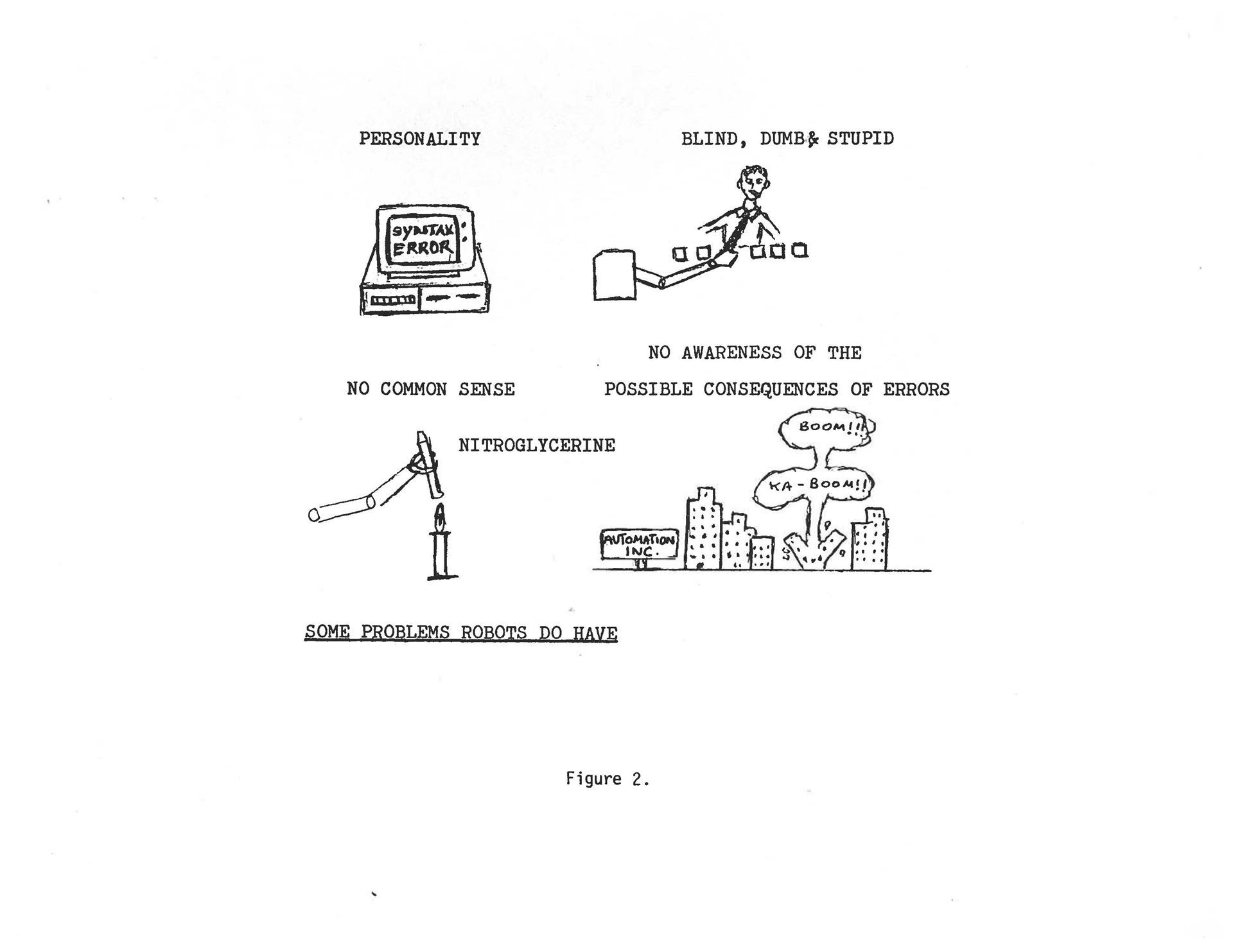

Alexander ScheelineSpectroclick, Inc.; Professor Emeritus, University of IllinoisFor approximately two decades, the most creative analytical spectroscopist and chemometrician in the western hemisphere was Tomas Hirschfeld. He was born in Uruguay, the son of Jewish refugees from Europe. The story is told that at age two, he queried his parents about why a vortex formed when the bathtub drained. In the mid-1960’s, Hirschfeld was part of the team at Block Engineering that produced the first commercial FT-IR based on a Michaelson interferometer and equipped with a minicomputer to process the data in real time. From there, he moved to Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), where he famously kept a filing cabinet, full of the ideas he hadn’t had the time to pursue. Because so many of the ideas were classified, everything in the cabinet was destroyed when he passed away.* Even so, he got dozens of patents and 5 "IR-100" Awards. He told people that if they were looking for interesting research ideas, they should either look at currently popular problems, or go back and read scientific papers from the 1930’s to find problems that had been technically impossible to solve then but had become tractable several decades later. Tomas gave excellent, informative talks, but with an irritating flaw: his slides were typically unreadable. He’d type up his slides, photograph them, and present the yellow-tinged result. The small font, grey-ish hue of the characters, and poor contrast made them useless! On the other hand, at FACSS 1985, he presented three adjacent posters, one of which featured a carousel projector and synchronized audio tape, with a photocopied handout of the presentation available, an early hint of what would later become “death by PowerPoint”. Several examples of TBH’s hand-constructed, and in some cases hand-drawn, presentation slides. Courtesy of M. Angel. He collaborated with many of the leading analytical chemists across the US. Jointly with Bruce Chase, he invented Fourier Transform Raman spectroscopy. With Gary Hieftje and David Honigs, he did some of the early principal component analysis of near infrared spectra. Because he was at LLNL, he worked on some defense projects about which his external colleagues knew nothing. He did, however, tell the world of one ingenious solution to a problem the US Air Force and Navy were having during the Vietnam War. Aircraft at first were able to fire flares to defend themselves from heat-seeking missiles. After some time, the flares ceased working. A desperate denizen of the Pentagon called Tomas and offered grant support for him to research how to defend against the missiles. While on the initial phone call, Tomas reported, “I figured out that the missiles were programmed to avoid heat sources that also generated visible light. So I told the general to just put a floodlamp on the back of the planes. After a short pause, there was a click – and no grant!” How many pilots knew that Tomas had saved their hides? Tomas was famously overweight and developed heart disease at an early age. He died of a heart attack in April, 1986. At the time, he was slated to give 8 presentations at FACSS XIII. A biography by H. M. Shapiro is available in Cytometry, 7, 399 (1986). Notice that my recollections say nothing of cytometry, yet that was one of the many fields he impacted. In addition to the award presented to an outstanding student by FACSS, there is a Tomas Hirschfeld Award presented by the International Council for Near Infrared Spectroscopy (ICNIRS). * Actually, this is not entirely true! See Mike Angel’s reminiscence here . |

Jonathan SweedlerJames R. Eisner Family Endowed Chair in Chemistry and Director, School of Chemical Sciences, University of IllinoisWhy I am an analytical chemist? One word: Hirschfeld! I have had an exciting and successful career as an analytical chemist, and yet when I began my undergraduate career at UC Davis, there were no analytical chemists on the faculty. While Dan Harris, who taught quantitative analysis at UC Davis at the time helped me see the light, the reason I made the career choices I did was because of Tomas Hirschfeld. During my freshman year (in 1980), I applied for a fellowship to spend a summer at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL). Like the other fellowship recipients, I got to select who to work with. For random reasons, I chose Tomas, and spent a total of three summers at LLNL working with Tomas. I may have been his first undergraduate student at LLNL. Tomas had a file cabinet full of one- to two-page “Tomas” ideas. Each summer he encouraged me to go through his idea drawer, pick out one or two to work on, and if he approved, those would be my summer project. His creativity and energy were boundless. It is during these summer internships that my enthusiasm for analytical chemistry exploded. One of many examples of TBH’s idea lists (updated along the way). Courtesy of M. Angel. Though Tomas kindled my analytical interests, he also almost ended them. I planned to present the results of my summer research at my first national scientific meeting in the Fall of 1982. Before heading back to UC Davis for the academic year, Tomas and I met to go over my talk and design the slides, which he would deliver to me in a few weeks, well before the meeting. When they didn’t arrive, Tomas kept assuring me they would show up. I still had the notes and slide drafts to practice on and so I thought all would work out. Well, the slides never came. Eventually, he promised to meet me in San Francisco on the Sunday before the start of the conference. But he did not show up! Monday afternoon, just before the session started, in walks Tomas with a grin, stating he had my slides, and not to worry, he had added some extras and they were great. He then loaded the carousal on the projector! Yes, my first scientific presentation included slides that I had never seen! I recall one slide in particular – I had no idea what it was showing. Not surprisingly, my presentation did not go well. This story is Tomas all the way. He could talk about any subject without preparation and assumed this was true of others. I have received multiple awards throughout my career, but receiving one of the inaugural Tomas B. Hirschfeld Scholar Awards (in 1987) remains especially rewarding. Many times in my career I have wished I could call Tomas and ask for his help with a difficult problem. In terms of critical thinking, imagination and innovation, Tomas Hirschfeld was exceptional. |

%20(1).png)